(Context: How to Establish Right Mindfulness)

Mindfulness of the body constitutes a sizable part of the establishment of mindfulness. When I was a beginner, I was surprised how much importance the Buddha placed in the mindfulness of the body. He said, for example, that:

Just as one who encompasses with his mind the great ocean thereby includes all the streams that run into the ocean, in the same way, whoever develops and cultivates mindfulness directed to the body includes all wholesome qualities that pertain to true knowledge.[1]

It’s that important. Wow. I had naively assumed that for any spiritual practice, the mind and “spirit” would take center stage while the body would have been a distant afterthought. But no, the Buddha puts mindfulness of the body right at the forefront of spiritual practice. I think the main reason is that Buddhism is, first and foremost, an insight tradition: Buddhism is concerned with developing the direct insight to see things as they really are, so as to understand the nature of suffering and liberation from suffering. A large percentage of our experience comes directly from the body. Therefore, one really cannot directly understand suffering and liberation from suffering without insight concerning the body. Another important reason to put mindfulness of the body first is that the body is very tangible, it has a physical presence, and it’s therefore much easier to place attention on a bodily object than something less tangible like a mind object.

Furthermore, the meditative skills developed from mindfulness of the body is transferable to other establishments of mindfulness. For example, by attending to the breath, one can develop relaxation and attentional stability. Once developed, those same qualities can be applied to mindfulness of sensations or mindfulness of mind. In that sense, mindfulness of the body facilitates all other establishments of mindfulness, and that’s why it eventually “includes all wholesome qualities that pertain to true knowledge.”

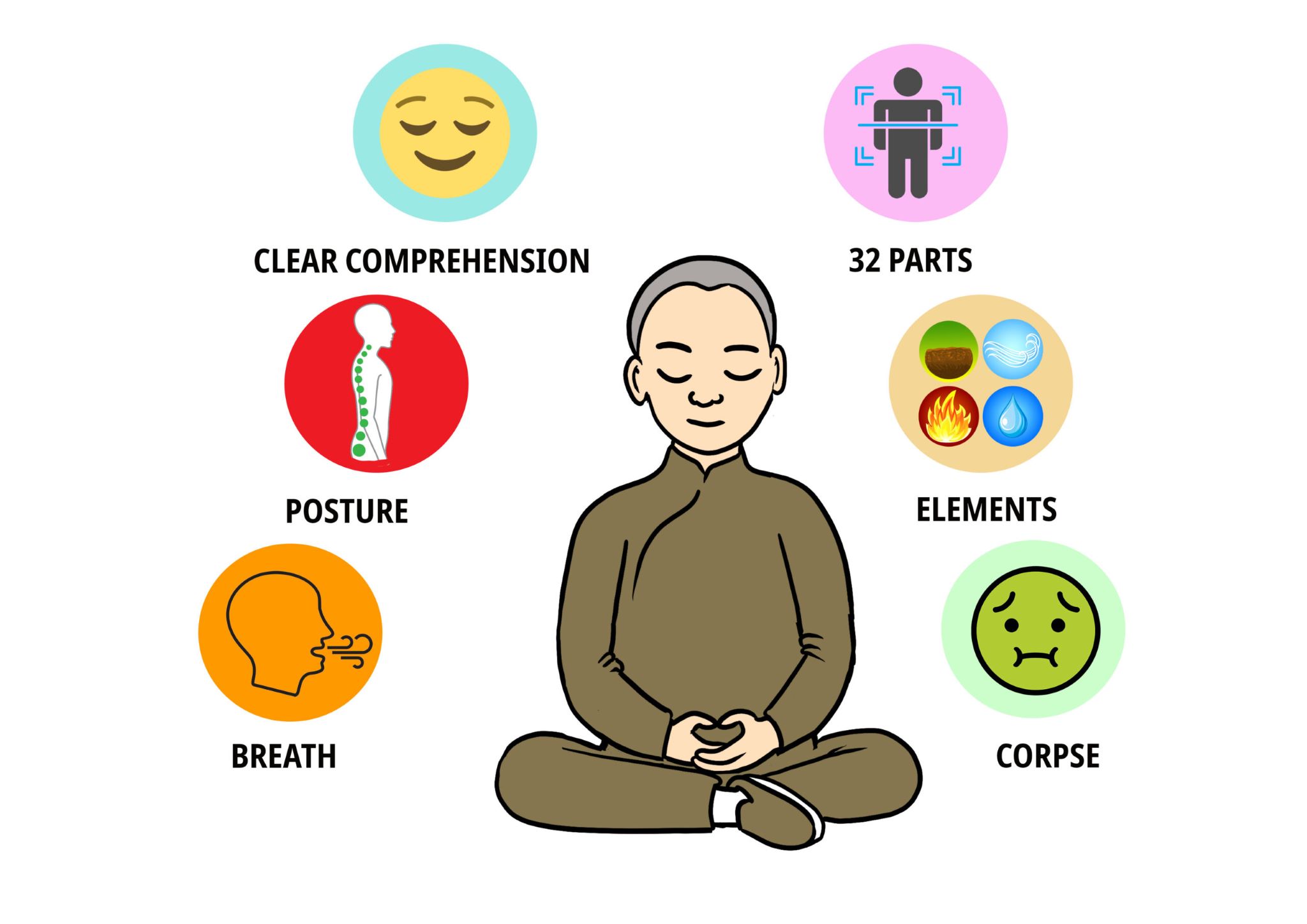

The Buddha suggests six meditation practices relating to mindfulness of the body. The first, and possibly most important, is mindfulness of breath, important enough that the Buddha devoted an entire discourse to it (unsurprisingly titled the Discourse on the Mindfulness of Breathing [2]) and explained how this one practice alone can lead to nirvana! The basic practice is surprisingly simple: know the breath at this moment, experience the whole body as you are breathing, and relax the body. That is all.

The second practice is also surprisingly simple, which is to just be mindful of your current posture. The Buddha specifically identifies four standard postures: walking, standing, sitting, lying down. The third practice is to engage in clear comprehension while in any posture and while performing any activity, including while falling asleep and waking up.

The next two practices examine the body in its component parts, and in doing so, you see the unattractive aspects of the body, thereby cultivating non-attachment to it. One practice scans the body, noticing 32 parts of the body (head-hairs, body-hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone-marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, contents of the stomach, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, spittle, snot, oil of joints, urine and the brain) and see that it is full of “impurities” and unattractive aspects. Another practice examines the body as containing the four elements as defined in ancient India: earth, water, air and fire, and once again, seeing its non-attractive aspects.

The final practice is kind of an extreme version of the previous two. It is called charnel ground contemplations. In ancient India, there were charnel grounds, which were places where human corpses were thrown and left to rot. This mindfulness practice is to go to those places, examine the corpses in various states of decay (“bloated, livid, oozing matter”), or see those corpses being devoured by birds, animals or worms, or see skeletons or disconnected human bones, and compare them to your own body and think, “My body too is of the same nature, it will be like that, it is not exempt from that fate.” Yes, this is a very much in-your-face kind of practice, it forces you to face the shocking truth of your own inevitable death and horrifying decay. I know, truth sucks.

These last three practices are also known as “asubha” practices. Asubha literally means “not beautiful”, but is often translated as “foulness” or “repulsiveness”. Asubha practices are often prescribed as an antidote against lust, and against attachment to one’s own body.

During the Buddha’s time, there was a very beautiful and famous courtesan by the name of Sirima. Sirima was very sick, and as she was being carried around, a young Buddhist monk caught a glimpse of her. He thought to himself, “Even when Sirima is sick, she is very beautiful.” He felt a very strong desire for her. That same night, Sirima died of illness. Four days later, her corpse started bloating and was infested with maggots. Taking advantage of the teaching opportunity, the Buddha asked King Bimbisara to announce that Sirima was available for a thousand coins. No man would take her for that price, or for five hundred coins, or two hundred and fifty, or for any price, or even for free. The Buddha then told his monks, “Look at Sirima. When she was alive, many men were willing to give a thousand coins just to spend a night with her, but now, none would even take her for free. The body of a person is subject to deterioration and decay.” And then he spoke in verse:

“Look at this dressed up body,

a mass of sores, supported (by bones), sickly,

a subject of many thoughts (of sensual desire).

Indeed, that body is neither permanent nor enduring.”[3]

When that young monk saw Sirima’s body and heard the Buddha’s words, he gained stream-entry.

Activities

References

[1] Aṅguttara Nikāya 1.575.

[2] Ānāpānassati Sutta (Majjhima Nikāya 118).

[3] Dhammapada 147. The story comes not from the canonical texts, but from Buddhaghosa’s fifth century commentary on the Dhammapada.

Featured image by Colin Goh.

Sharing Joy and Wisdom with our Buddhist Art

Our team is honored to work with talented artists to create meaningful Buddhist art. To share these creations more widely, we are offering them on thoughtfully crafted merchandise. We hope these items can serve as gentle reminders and companions to inspire wisdom, compassion, and joy in daily life. [Learn More].

Explore our entire Buddhism.net collection here.

Explore the Mindfulness of the Body design collection here.

Merchandise highlights from this design collection