There is a particularly powerful form of grasping that relates to all three forms of craving, and also relates to the “five aggregates subject to grasping”. It is grasping to the five aggregates as “this is mine”, or “this is me”, or “this is my soul.”

For example, we identify this body as mine. Mine! Or, these thoughts and emotions as me. Me! Or, this consciousness is my soul. My soul! In other words, we grasp on to selfness. We like to think that selfness is something that is rock solid, that we can rely on, that we have ownership of, and sovereignty over. That is suffering because selfness can offer us none of those things.

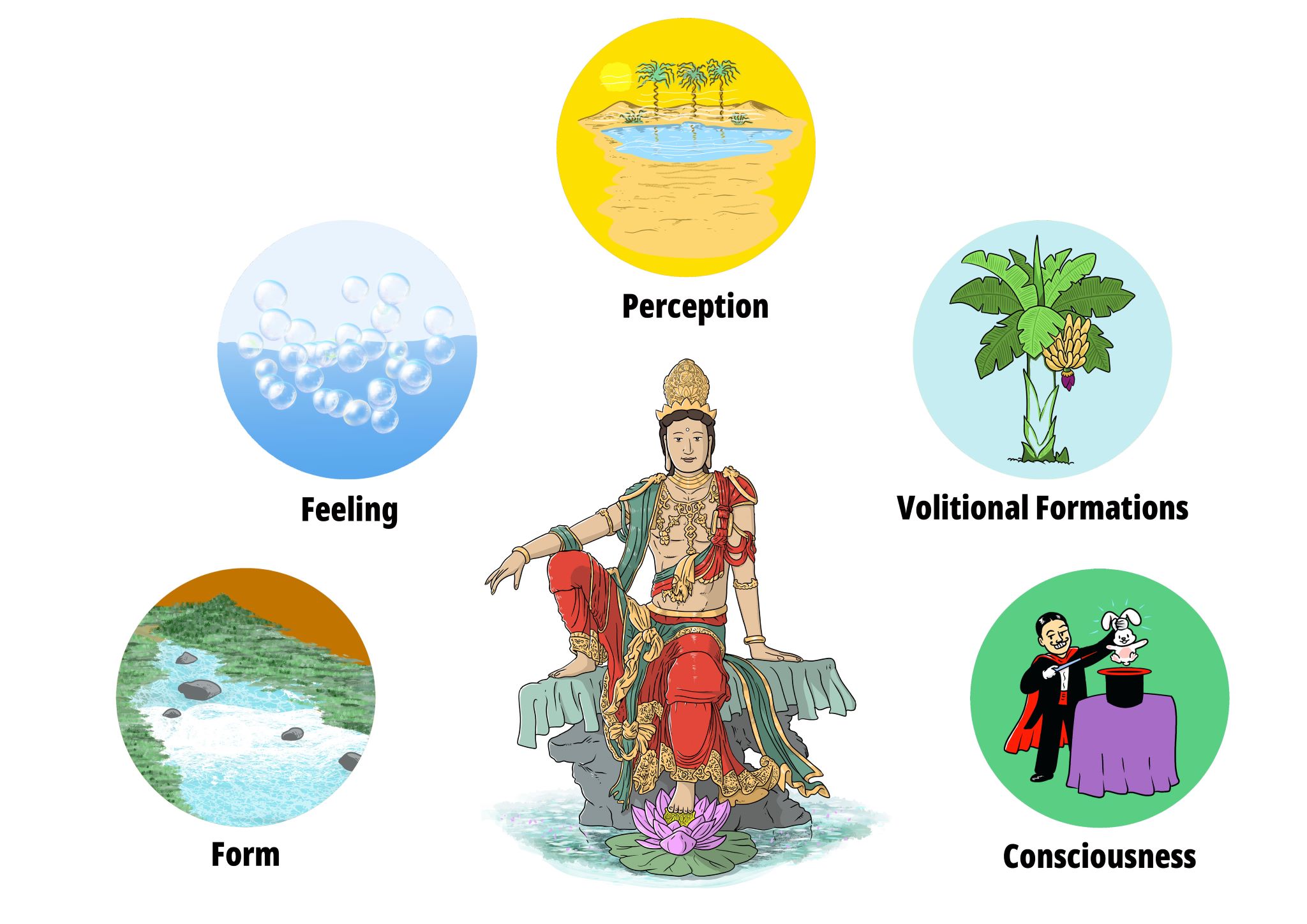

In the famous Discourse on A Lump of Foam[1], the Buddha compares bodily form to a lump of foam floating on the river: it appears substantial at first, but when properly inspected, one would find it to be “void, hollow, insubstantial.” In the same way, all the other aggregates appear to be substantial but, when carefully inspected, are shown to be void, hollow, and insubstantial. Sensation is compared to water bubbles: they look real, but they form and disappear very quickly. Perception is compared to a mirage, it looks real, but it is nothing more than a projection.

The analogy for volitional formations is extra interesting to me because it involved something I did not know: that a banana tree does not actually have a trunk. In fact, a banana tree is not even a tree, it is a giant herbaceous plant with large leaves that roll up tightly one over another in a way that makes them resemble a trunk. A man who needs heartwood for construction might cut down a banana tree, but he will soon find that there is no useful heartwood there at all, merely a roll of giant leaves. Similarly, thoughts and emotions may seem real, but when investigated closely, they turn out merely to be creations of mind: insubstantial and often not particularly useful.

Finally, and this is one of Soryu’s favorite analogies, the Buddha compared consciousness to a magician’s illusion. Everything a magician does looks so real. It looks like he really made a ball disappear and then reappear somewhere else. It looks like he really cut a woman into two, and then put her back together. But they are all just deceptive illusions. Similarly, consciousness appears substantial, but when it’s investigated, nothing is found that has any substance.

Every aggregate, when closely investigated, is shown to be void, hollow, and insubstantial. Buddhist teacher Shinzen Young has a very nice description of selfness: “The experience of self is a process, and there is no thing in that process that is a self.” Due to its insubstantiality, grasping on to any aggregate as mine, me, or my soul results in suffering.

Do not worry if you do not fully understand this yet. This is profound stuff, which we will talk about again later in this series as you learn more about Buddhism. Think of this post as like an introduction to a very deep person: it is good enough to just meet her now, and you will have plenty of chances to talk to her later.

How profound is this stuff? It is enough to trigger full enlightenment. In a particularly important discourse called the Discourse on the Characteristics of Not-self[2], the Buddha spoke on this topic. This was his second discourse after his enlightenment, and it was delivered to these five original monks. The Buddha said:

Any kind of form, or sensation, or perception, or volitional formation, or consciousness, whatsoever, whether past, future, or present, internal or external, gross or subtle, inferior or superior, far or near, all should be seen as it really is with correct wisdom thus: ‘This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.’

With that, one becomes no longer enchanted by the five aggregates. With disenchantment comes liberation. At the end of the discourse, all five monks attained full enlightenment.

You may ask, what is the difference between “I” and “my self”? When the Buddha used the word self (atta) here, he meant it in a way that may be different from how modern people understand it. In the Buddha’s time and place, one popular belief was we all have a core self that is permanent, unchanging and inherently blissful. Many modern people call that the soul. During the Buddha’s time, the word used to refer to this soul, atta, was the same word used for self, hence the translation to “self”, but in this context, it should read as “soul”.

The Buddha states that no one, not even God, or the universe, or nature, has a permanent, unchanging and inherently blissful soul, and that none of the five aggregates, nor any combination of them, constitutes that permanent, unchanging and inherently blissful soul. Instead, it is precisely freedom from any identification with a self that is release from suffering and the realization of true bliss. This is the teaching of non-self (anatta). It is one of the most important teachings in all of Buddhism.

There is an important nuance relating to grasping. While the English word grasping means to hold tightly on, the Pali word for grasping, upādāna, also means fuel.[3] This is the vitally important nuance that is lost when translated to English: whatever you grasp on to also fuels the one who is grasping. That which one grasps onto is also the basis of the one who grasps. The ancient Indian analogy is that of a fire. In the ancient Indian perspective, the fire “grasps” to the fuel at the same time that the fuel sustains the fire.[4] A modern analogy is addiction. Addiction can be seen as grasping on to the substance one is abusing, but the very act of abusing that substance fuels the grasping itself. What makes this insight so vitally important is its consequence: once you release the grasping, you also let go of the fuel that supports the grasping itself. Therefore, the choice of releasing the grasping sets off a virtuous cycle that eventually removes the very support for the cause of your suffering.

Soryu says that you can also think of the five aggregates as being the fuel for the sense of self. When we try to use them as fuel for selfness, or as support for selfness, we are clinging to them. That is suffering right there. Most people have the opposite belief, they believe that grasping is safety, but the Buddha points out that grasping is actually suffering. Think of a drowning man grasping desperately on to a heavy sinking object believing that the grasping will provide him safety, but in reality, real safety begins with letting go.

The most important consequence of this teaching is it shows you where your power lies. It turns out that you can choose not to grasp on to the aggregates as mine, I or my self. That choice can yield freedom from all suffering. Later in this series, we will talk about how to develop the ability to make that choice.

Activities

References

[1] Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta (Saṃyutta Nikāya 22.95).

[2] Anatta-lakkhana Sutta (Saṃyutta Nikāya 22.59).

[3] More formally, “that [material] substratum by means of which an active process is kept alive or going.” See The Pali Text Society’s Pali-English dictionary. Chipstead, 1921-1925.

[4] Richard Gombrich, How Buddhism Began. Routledge (2011).

Featured image by Colin Goh.