If I ever give you the mistaken impression that virtue is merely the preparation for meditation, and that meditation is the “real Buddhism”, then you should scold me and call me funny names. In truth, virtue is a powerful and essential component in every step of the training.

Virtue is inherently life-changing

First, virtue is life-changing in and of itself. Even if you cultivate no samadhi and no wisdom, if you cultivate only virtue, that alone creates its own sustainable source of happiness. Better still, it works on a number of levels. For example, take the simple virtue of generosity. On the lowest end of the spectrum, if nothing else, the Buddha reminds you that practicing generosity makes you dear to people, and helps you gain a good reputation.[1] Beyond that, you bring benefit to others and you feel better about yourself. Even beyond that, it helps you cultivate kindness and compassion and, therefore, directly helps purify your mind of ill-will. But even beyond that, it weakens your craving and strengthens your ability to let go and, therefore, makes a direct contribution to your journey to nirvana.

All virtues possess a similar spectrum of life-changing benefits, ranging from totally worldly stuff like improving your social standing, to helping you gain inner happiness, to helping purify your mind, and all the way to helping you arrive at nirvana. All that, and it benefits people around you. So, if you do nothing except cultivate virtue, and even if you cultivate only a single virtue, it will bring happiness to you and the people around you.

Virtue sets you up for samadhi

Beyond its inherent value, virtue also very importantly sets you up for samadhi, and it does so in two ways. First, it gifts to you a mind that is largely clear from gross mental afflictions such as lust, envy, anger, hatred, and regret. It is like a farmer clearing the ground of rocks and large stones before ploughing, it makes the process a lot smoother. In the same way, the more your mind is free from gross mental afflictions, the more easily it can get into samadhi. Second, inner joy is highly conducive to samadhi. The Buddha even says that the direct cause for samadhi is happiness[2], specifically the type of gentle happiness that comes from wholesome sources that are not polluted by afflictive mental states such as lust or anger. Virtue is a bountiful source for that type of happiness. Hence, the more virtue you have, the more wholesome happiness you possess that turbo-charges your samadhi.

Virtue helps you relinquish craving

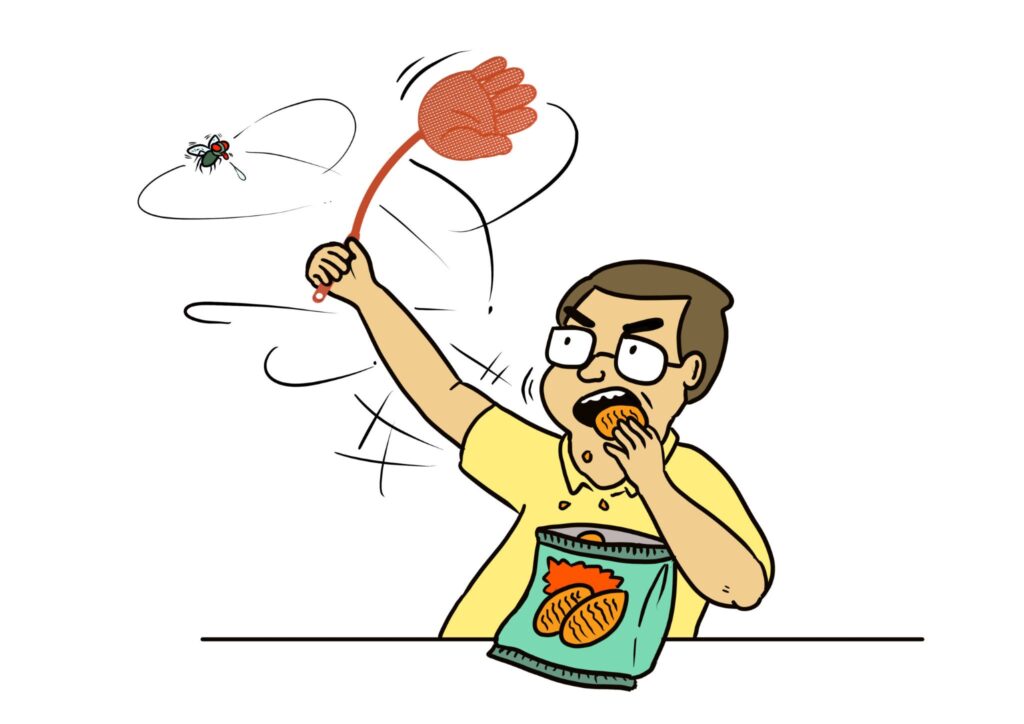

Compelling as that might be, virtue works on an even deeper level. Remember that in the Second Noble Truth, the Buddha identified craving as a necessary cause of suffering? Virtue turns out to be an awesome power tool when it comes to relinquishing craving, by providing you with an honest, objective measure of how well you are really dealing with craving. That is because behavior can be observed far more objectively than inner mental states. Let me give you an example. Say you enjoy killing mosquitos but, inspired by virtue, you want to closely observe the first precept to refrain from killing even mosquitos. Let’s say you learn meditation for a while, and then I ask you a self-perception question, “Do you feel that your craving for swatting mosquitos is weaker now?” It is remarkably easy to fool yourself. If, instead, I ask you a behavioral question, “Are you now able to stop swatting mosquitos?” This question has a very objective answer, because you either swatted a mosquito, or you did not; there is no space for subjective interpretation. In that sense, behavior is the most objective aspect of the mind.

Now, because you are trying to not swat mosquitos, you have to address the underlying strands of craving that makes you want to swat them. The main one is the craving to avoid the physical discomfort of itchiness from mosquito bites. So much discomfort! And then maybe there are subtler strands of craving, such as the feeling of power and the pleasure of “revenge” experienced when swatting mosquitos. In addressing all those strands of craving, you need to deepen samadhi to the point where that sensation of itchiness is experienced merely as sensation, and no longer as suffering, at least during formal meditation.

In short, in this process, you start with trying to fulfil the virtue of not killing even mosquitos, and you end with cutting various strands of craving and reducing your own suffering, with the number of mosquitos you do or do not swat from now on as the convenient measurement of progress.

This process works for anything at the intersection of virtue and craving, such as consuming alcohol and drugs, the temptation to lie, or steal, or give in to sexual misconduct.

Why is that important? There is a popular saying, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure.” In organizational management and in engineering, the first step in managing any process is to measure it. In relinquishing craving, the best measure of how well you are doing is how it shows up in behavior change. The better you can measure it, the better you can manage it.

Virtue gives you the struggle to enable growth

Once upon a time, a young boy witnessed a butterfly struggle for hours to break free from its cocoon. Eager to help, the boy took a pair of scissors and cut a large slit on the cocoon. The butterfly emerged, but it was unable to fly. Why? Because the butterfly needed that struggle in order for its wings to be filled with blood and to gain strength. Without the struggle, the butterfly will emerge unable to fly.

There are many processes in nature that require struggle to facilitate growth. The butterfly is one example. Another example is physical training. To grow bicep muscles, you have to do bicep curls to the extent that you struggle to do the next repetition. The body then responds by growing the muscles.

Struggle turns out to also be highly conducive to spiritual growth, and virtue provides that struggle. Anybody who sincerely tries to practice virtue soon learns that it is a struggle. Once upon a time, there was a city where police corruption was rife. One year, the lone uncorrupted police inspector was assigned a few fresh graduates from the Police Academy. He asked each of them in turn, “Will you be able to always do your job with the utmost integrity?” Everyone confidently shouted back, “Yes, sir!” Everyone except Sam. Sam answered, “I don’t know, sir, I will try, but it sounds really hard.” The police inspector shook his head. Everybody laughed. Years later, every single one of those fresh graduates turned corrupt, except for Sam. The old police inspector went to see him and said, “Do you remember the question I asked you on the first day you reported to me? That was the day I knew I could trust you. Because you said doing your job with the utmost integrity sounded really hard. That meant that, unlike the others, you were actually going to try. I know that because I have been doing this for decades, and every day of upholding the highest integrity is still very hard for me.”

It gets worse. Those who persist in perfecting their virtue also soon learn that things are not usually black and white, and no matter how virtuous they already are, they will find it a continuing struggle, often with no good solutions. Take for example, the very first precept: the precept to abstain from killing. At first, I was like, pffff, easy peasy, I have never killed anyone or anything in my life, except occasional bugs. There, done, I’m home free! But wait, are bugs not sentient life? Well, of course they are, duh. What about all the meat and fish I eat? Is life not taken on my behalf? Okay, but what if I become vegetarian? And then one of my Tibetan Buddhist teachers reminded me that agriculture involves killing a lot of “pests” as well, therefore, merely by eating, I am responsible for second-hand killing. It turns out there is no good answer. For that teacher, her answer was the solemn recognition at every meal that, “As long as I have to eat, some other sentient beings will die. Therefore, I dedicate my life to my own liberation and the liberation of all sentient beings.” I find that a beautiful answer.

Soryu says as beautiful as that answer is, that is not the main point. Like the butterfly in the cocoon, the main point is the struggle itself. It is the aspiration to live a completely virtuous life, no matter how “unrealistic” it may appear, and the willingness to face, with brutal honesty, this question: what is my inner obstacle to complete virtue? That question is important because its answer illuminates the next stubborn strand of craving to cut. Or, more accurately, that obstacle illuminates the next growth opportunity. Here again, virtue helps you to relinquish craving. Every time another strand of craving is weakened or cut off, samadhi and wisdom deepen more, you become happier, and you live a more virtuous life. If you follow your commitment to living complete virtue, you will then have to struggle with the next obstacle, which presents the next growth opportunity, and so on. That is how the continuous struggle toward complete virtue continuously offers up new opportunities for spiritual growth.

It is not just eating. Constructing buildings also causes loss of life and environmental damage. Same with using products, or taking transportation. And then there are livelihood-related questions such as: should I continue working in the arms industry, or in an industry that contributes to environmental destruction? To be clear, Soryu does eat food, live in a building, wear clothes, own a laptop, and use transportation (I checked). It is not that we stop doing those things. It is that we are always aspiring to live a life of maximum virtue, even if we do not know how to overcome the obstacles to it, and that we are always willing to experience that difficult struggle internally to achieve maximum virtue. The more honest that struggle is, the more spiritual growth is facilitated.

Soryu offers us a deep point to contemplate. He says:

The depth of the struggle predicts the depth of the realization. The more you struggle, the more deeply you will awaken. You may need to take this on faith right now, but I assure you that to struggle in this way allows you to realize a new kind of joy, and that joy facilitates realization. The joy we can experience from struggling with ethical questions is greater than any joy anyone in the world can ever experience through getting what they desire. Because we experience this joy, we enter deep samadhi. Because we enter deep samadhi, we discover wisdom. Because we discover wisdom, we are liberated. The depth of joy predicts the depth of wisdom. Therefore, the depth of struggle predicts the depth of realization.

Virtue shows you that you can walk the path

Virtue is so powerful in so many areas it is hard to pinpoint one thing and say, “This is the most important thing it does for you.” But if I have to choose, this could be it: it shows you that you are indeed capable of walking the path.

I was a prominent member of a movement to make mindfulness widely accessible in secular settings. A few of my friends started a very noble project to teach mindfulness, for free, to women in highly disadvantaged backgrounds who lost their jobs. The idea was that maybe if they learned mindfulness, it would help them do better in job interviews. At the end of the course a few weeks later, many of the women offered their testimonials. One of the testimonials was so powerful it brought people to tears, and it didn’t even have anything to do with job-hunting. The woman simply said, “Since I started learning mindfulness, I no longer beat my kid.”

A powerful feature of the Buddhist practice is it gives you the ability to live more virtuously. In the case of this woman’s story, there is no doubt that she would rather not beat her kid, but rising to that virtue was too hard for her. Once she practiced even just a few weeks of relatively shallow mindfulness practice, she developed the ability to rise to that virtue. It was life-changing for her, and for her child.

So, the practice allows you to become more virtuous. That virtue then gives you the confidence that you can do the practice. This is a virtuous cycle.

There are many people who understand and accept the Dharma, but choose not to practice it anyway. That is because they have a deeply held belief that they are incapable of walking the path, and therefore, they will not even try. That is where virtue comes in. It shows you that you can do it, and it does so in two ways.

First, virtue shows you that you have more power than you knew. The woman in the story above, for example, found that she had the power to not beat her kid, which was way more power than she imagined she had. Let me also share another example. Imagine that you had an addiction to snacking (this example, by the way, is based on the embarrassing true story of one of this series’ two co-authors, and it is not Soryu). You went to see a doctor and he informed you that you were developing health problems, and that you had to cut down on your snacking by at least half. Ouch. You obeyed your doctor’s orders because you were too afraid to, you know, die. Six months later, your blood tests showed that those health problems were gone. Woah. Besides better health, you gained something else: self-confidence. By being able to half your snacking for six whole months, you showed yourself that you have some power over desires. You proved that you do not have to always be the slave of your desires. You have the power to transcend yourself. That gives you confidence.

In life, it is often very easy to know what the right thing to do is, the hard part is actually doing it. For example, when I was addicted to snacking, I knew for certain that the right thing to do was to drastically cut it down, but actually doing it was too hard. Same with lying to get out of trouble, and a whole host of other stuff. The gift that virtue gives us here is every time we succeed in doing the right thing, it gives us more confidence that we have the power to transcend ourselves. And confidence in being able to transcend oneself is one of the most important conditions for staying on the spiritual path.

I discovered my own power in a similar way the woman in the story did. When I first started doing the practice, my motivation was entirely utilitarian: all I wanted to do was to escape from misery. And then I discovered that not only was the practice able to do that, it had the totally surprising “side effect” of making me a better human being. I did not ever imagine myself becoming a better person. I saw myself a useless weakling in the face of temptation and my worst impulses, but there I was, with every little bit more practice, becoming less weak, less useless. It was like when I was a kid, I was a skinny weakling bullied by the bigger boys, but the better I became at karate, the less of a weakling I became, and I gained that confidence in my training and in myself.

The second thing virtue does for you is it shows you that you are, in truth, a good person. Look, we all want to be happy, and for many of us, the most obvious path to being happy is to do things that feed us with sensual and egoistic pleasures, often at the expense of virtue. Imagine that one day, you find that being virtuous gives you more happiness than that. For example, pretend you were a selfish person, and then you tried being charitable, and then you realize after a while that being charitable makes you significantly happier. What does that say? It says that you are a better person than you imagined, because you are, by your very nature, the type who gains more happiness being charitable than selfish. It says that your original assumption about your nature may be wrong. Whatever story you spun to malign yourself, it turns out that you are, at your very core, a good person. The self-narrative then goes from, “I am a lousy person incapable of enlightenment who is better off just indulging” to, “I am an imperfect but fundamentally good person, a work-in-progress, continuously learning to expand and express my goodness.” That changes everything. Virtue gives you that gift.

Later in this series, we will share the true story of the spiritual journey of a modern seeker on her path to directly seeing nirvana, and one thing that may surprise you is how often she got stuck. In every case, one of the most important things that got her unstuck was her training in virtue. That is because virtue demands self-honesty, and it yields self-confidence, so the deeper her training in virtue, the stronger those two qualities become. Every time she was stuck on her spiritual path, she needed total self-honesty to assess her situation, and the self-confidence to say, “I can move forward.” And that was how her training in virtue helped get her unstuck every time.

Actually, virtue is essential in everything

If you are already sold on the awesome power of virtue given everything we said, this is the part where we go, “But wait, there is more!”

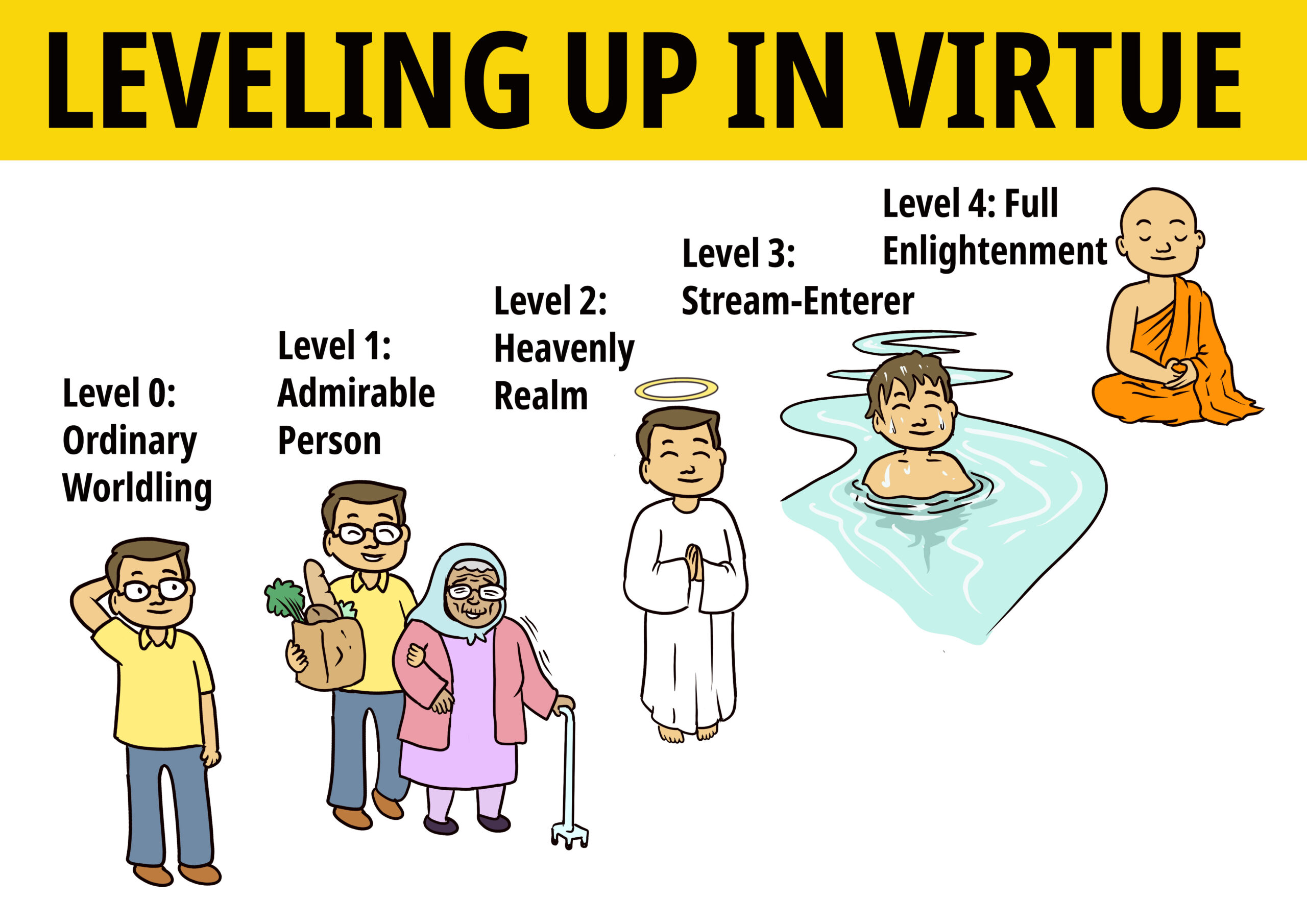

Virtue is not just an amazingly powerful tool on your spiritual path, it is an essential element of the entirety of your spiritual path. This is expressed beautifully in a later Buddhist text[3], that states that if you deepen your virtue sufficiently, you cease being an “ordinary worldling”, and you become an admirable person. If you deepen your virtue further, you can upgrade from being a worldling, because you are walking a path that will lead you to a heavenly realm after you die. If you deepen your virtue even further, you can use it as a basis to gain enough samadhi and wisdom to gain stream-entry. And then if you deepen your virtue even more still, it is the basis of enough samadhi and wisdom to gain full enlightenment.

If you remember only one thing about virtue, remember that virtue gives us the bliss of blamesslessness, and that the bliss of blamelessness can be cultivated far beyond what sensual pleasure can offer us. Once you are able to do that, everything else eventually falls into place.

The entire spiritual path is by virtue of virtue.

But what, there is more! Your virtue also benefits society. Coming up in the next article.

Activities

- Reflect on this post with Angela:

- One way to know whether these teachings are true for you, is to practice them! Start cultivating virtue, and observe if your life gets better, if you start to experience the bliss of blamelessness, and if your mind increasingly inclines towards samādhi and wisdom. If and when misfortune hits you, you will have a ready mind to meet life as it is.

- What is virtue to you? Why is living a virtuous life important and beneficial?

- What habitual patterns do you have that are unvirtuous? How might you break these unvirtuous habitual patterns? Why is being free of unvirtuous habits important?

References

[1] Aṅguttara Nikāya 5.35.

[2] Upanisa Sutta (Saṃyutta Nikāya 12.23).

[3] The Flower Garland Discourse (Chinese: 华严经, Sanskrit: Avataṃsaka Sūtra). Specifically, this is in Chapter 26, Part 2 (which is confusingly in Scroll 35), on the Ten Stages (十地品).

All images by Natalie Tsang.