(Context: The Buddhist Path is Filled With Joy)

The inner joy of the jhānas plays a very important role in the joyful path. In fact, the joy of the jhānas is one place where the genius of the Buddha shows up. See, since those states of right samadhi are inherently joyful, there must have been a level of fear that a meditator can become attached to them, get stuck there, and hence not be able to advance into higher wisdom. We know even Siddhattha (before he became the Buddha) had that concern because just before he decided to go into the jhānas on the night of his enlightenment, he had to ask himself, “Why should I be afraid of the inner joy brought about by the first jhāna?” And then he realized, “That joy has nothing to do with sensual pleasure or unwholesome mental states, so I should not be afraid of it.” With that insight, he became willing to get into the jhānas in pursuit of wisdom.

In a conversation with a novice named Cunda,[1] the Buddha addressed this issue head on, and then some. He told Cunda that the indulgence in the pleasure of the four jhānas “are entirely conducive to disillusionment, dispassion, cessation, peace, insight, awakening, and nirvana.” Why? Because those pleasures are “detached from all sense desires and unwholesome mental states.” He also told Cunda, “If the followers of the other sects were to accuse you [Buddhists] of living indulgent in the pleasures of the jhānas, you should tell them ‘Exactly so!’” As if that was not shocking enough for novice Cunda, the Buddha added the kicker, “Anybody who lives indulging in the pleasures of the jhānas can expect one of four outcomes: he becomes a stream-enterer, once-returner, non-returner, or arahant” with the destruction of the fetters.[2] Cunda probably had to pick his jaw up from the floor.

Having said that, yes, it is possible to get attached to the jhānic joys and then get stuck in your spiritual progress. The Buddha warns about it, he calls it “being stuck internally”,[3] which is described as, “if a meditator’s consciousness follows after the meditative joys and is tied and shackled by their gratification.” When the Buddha tells the monks to “indulge in pleasure of the four jhānas”, he means to do it without being tied and shackled by their gratification.

Soryu nonetheless makes the point that this isn’t a great concern for two main reasons. First, while it is true that the pleasure of jhāna is more fulfilling than sensual pleasure, it is of its own nature far less addictive. Actually, in an almost funny way, that’s the reason it is so hard for most people to enter it. Most of us are slaves to our addictions. Therefore, we get lost in the small pleasure of thinking, which is very addictive, rather than the deep and vast pleasure of jhāna, which is much less addictive. Second, the pleasure of jhāna is healing. It releases us from our fixations and lets our bodies relax so that the tension that holds us captive can release. For these reasons, Soryu and I definitely disagree with modern teachers who warn students against practicing right samadhi for fear of being addicted to the pleasure of jhāna. To them, we say, “Dear friends, remember that the Buddha never said that right samadhi is optional. The sheer power of right samadhi to propel a student towards nirvana is far more advantageous compared to the small risk of the student getting stuck in it. Furthermore, that risk is highly manageable with a good teacher.”

In another discourse, the Buddha frames the power of jhāna for enlightenment in a different way. He talks about a hard path to liberation (which he calls the path “through volitional exertion”) and a comparatively easy path (the path “without volitional exertion”). The easier path is the one with the jhānas. He says:

“How, monks, does a person attain nirvana through volitional exertion? Here, he dwells contemplating in unattractiveness, repulsiveness, discontent, impermanence, perception of death. He dwells relying upon the five powers of a trainee: faith, moral shame, fear of wrongdoing, energy and wisdom. These five faculties then become extremely strong in him: faith, energy, mindfulness, samadhi and wisdom. Because of the strength of these five faculties, he attains nirvana.

How, monks, does a person attain nirvana without volitional exertion? Here, he enters the four jhānas. Thereafter, he dwells relying upon the five faculties of faith, energy, mindfulness, samadhi and wisdom. Because of the strength of these five faculties, he attains nirvana.”[4]

Modern teachers interpret the above passage in one of two ways. The first is that it is entirely possible to reach nirvana without the jhānas, but it is hard and painful (unless you find volitional exertion to be fun, like Soryu does). The second interpretation (the one favored by Soryu) is that right samadhi is unavoidable on the way to nirvana, and you either experience it organically for at least a short time before seeing nirvana, or if you choose, you can traverse the path with it. And since you will experience it anyway, you might as well traverse the path with it, because it makes the path so much easier.

In either interpretation, the conclusion is the same: the scenic path through the jhānas is more fun and much easier. The discovery of the scenic path is pure genius.

This is not to say that the unpleasant things listed here by the Buddha on the harder path are bypassed by those taking the easier path. For example, the jhāna practitioner will still end up eventually having to contemplate unattractiveness, impermanence, perception of death, and so on. However, the jhāna-equipped mind will find the process much easier and far more pleasant. As you will see later in this series, when the modern student Susan, who had mastered the jhānas at this point, fully experienced impermanence and all, that experience was described as, “This is both horrifying and the most pleasant and wonderful experience of a person’s life up to this point.”

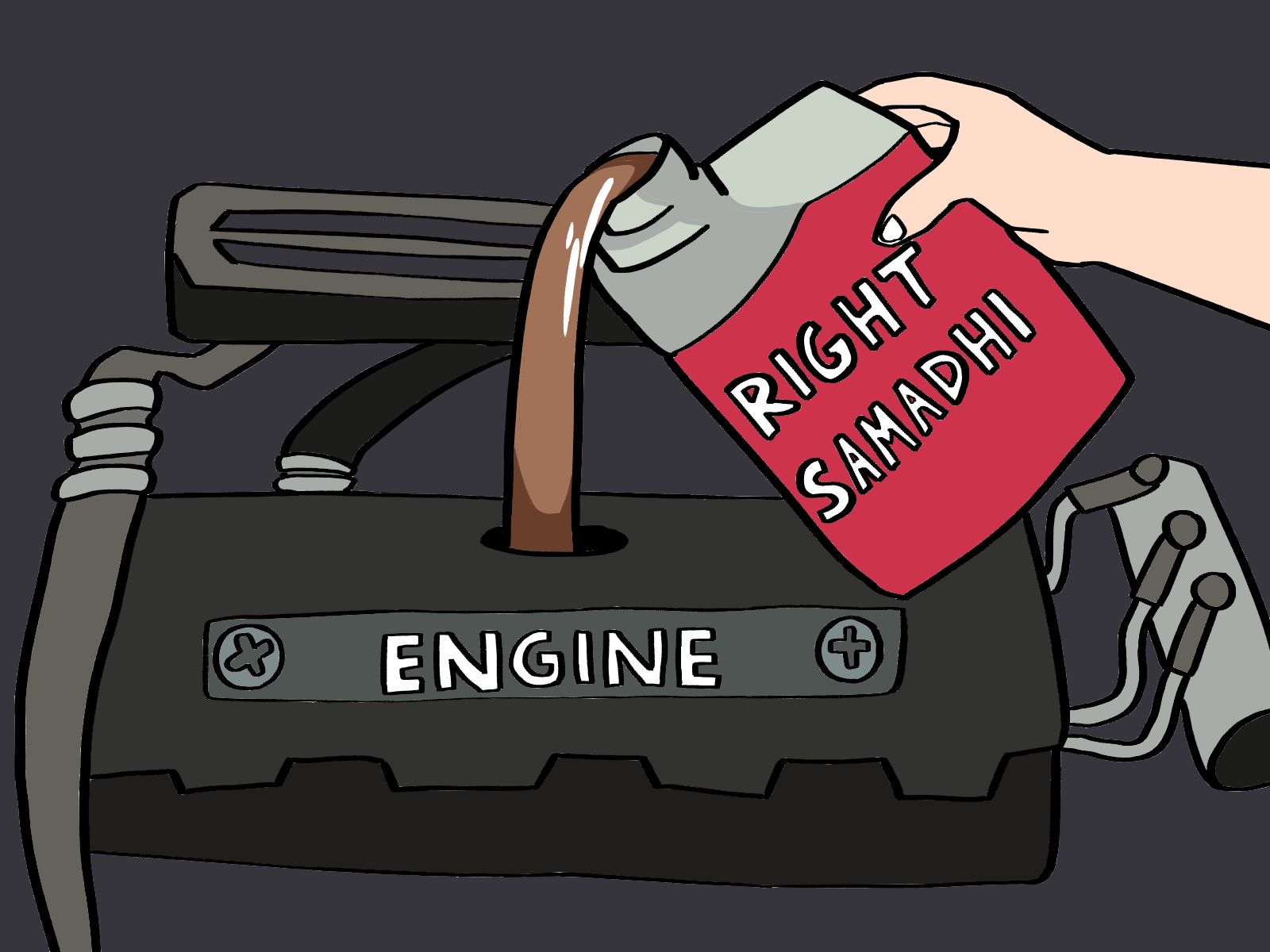

In that sense, the joy of right samadhi is like grease on an engine. You are taking a trip to nirvana, that engine takes you there. As the engineer, you can either grease the engine or not. If you do not grease the engine, it will grind, overheat, and make horrible noises, and worse, you risk a total engine breakdown. With grease, you still make the same journey using the same engine, but the trip is much more pleasant.

Soryu and I have both studied the entire corpus of the early Buddhist discourses, and we are not aware of even a single instance where the Buddha talked about his system of training without including right samadhi. I.e., there is not a single case where the Buddha said right samadhi was optional in the training. That leads me to believe that the Buddha was like the type of engineer who always greases his engines. That warms the heart of this old engineer.

Activities

- Reflect on this post with Angela:

- Joy is essential for our experience of day-to-day life; likewise, joy is a very important friend on our spiritual path.

- Why is joy important in your life, and in the spiritual path?

- How can you incline your mind towards joy?

References

[1] Pāsādika Sutta (Dīgha Nikāya 29).

[2] On fetters and the four stages of enlightenment, see this post.

[3] Majjhima Nikāya 138.

[4] Aṅguttara Nikāya 4.169.

Featured image by Natalie Tsang.