(Continued from The Buddha Formerly Known As Prince.)

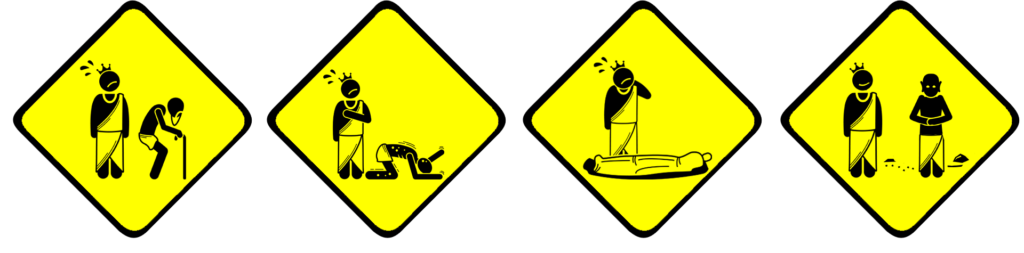

One glorious day, Siddhattha went into town with his charioteer Channa, and came into direct contact with the stark realities of real life outside his pampered existence. It shocked him to his core. On this trip, he saw four things that changed his life, that would later be known in Buddhism as the Four Sights.[1]

First, he saw a decrepit old man, and he suddenly realized that he himself was subject to aging, and that everybody else was also subject to aging. Next, he saw a very sick man, and it suddenly dawned on him that he was subject to sickness, and so too was everybody else. The third sight must have been the most shocking of all: he saw a corpse. He realized that someday, he would be just like this corpse. Someday, he would die, and that everybody else was also subject to death.

While the first three sights shocked and depressed him, the fourth offered him hope. The fourth sight was that of an ascetic, one who had renounced the world to devote himself to finding the truth. Siddhattha must have been impressed by the calm and dignified demeanor of the ascetic, for after seeing this man, he decided that he too wanted to follow that career path.

Having seen suffering, Siddhattha decided that the most noble thing to do was to find the solution to all suffering. Much later (after his enlightenment), he would tell his disciples that a “noble search” was one where someone subject to birth, aging, sickness and death seeks a solution to those things.[2] He was determined to begin his own noble search. The admission price of Siddhattha’s noble search was giving up of his family life and his pleasure-filled, princely existence. He was willing to pay that price.

It is remarkable that Siddhattha chose to pay the heavy price of renunciation. Being a prince, his obvious choice would have been to hire one or more holy men to teach him while continuing to live his luxurious life, as many aristocrats, princes, kings and emperors had done all thorough history. Yet, Siddhattha decided to go all-in, renouncing all that he had, and to live the holy life. Why? It was because Siddhattha made a notably astute observation: it makes no sense for one seeking the solution to birth, aging, sickness and death to seek anything that is also subject to birth, aging, sickness and death.[3] It is one of those insights that takes wisdom to see, but once you see it, it becomes so obvious you wonder why it was not always obvious before. Siddhattha had the wisdom to see it for himself. Beyond wisdom, Siddhattha also had courage. If you are rich and powerful, it takes a lot of courage to give up everything you have in pursuit of a noble search, and Siddhattha had it in him.

Not long after Siddhattha made the decision to renounce his worldly life to become an ascetic, he received news of the birth of his son. According to popular lore, upon hearing this news, he remarked, “An impediment – rāhu, has been born; a fetter has arisen”, hence the infant was accordingly named Rāhula by his grandfather, the king. Though this story is very popular, it is actually not found in the canonical texts. It is much more likely, according to modern scholars, that Rāhula was named in accordance with an eclipse of the moon, rather than as an “impediment”.

It is useful to understand Siddhattha’s decision to renounce from the lens of compassion. Like a modern-day father who leaves his family to work in a foreign country for many years to elevate his family out of poverty, Siddhattha had to take on a multi-year ascetic assignment away to elevate his family (and all sentient beings, for that matter) out of suffering. Even though Siddhattha loved his wife and newborn son, his compassion for them and for all sentient beings compelled him to leave his family to embark on his noble search for the solution to all suffering. He simply had to do it. It helped that his wife and son, being royals, would be well taken care of by the extended family in his absence. One day, he made the final decision to leave in the middle of the night. On the night of his departure, he opened the door to his bedroom and took one last look at his sleeping wife and child.

And then he left quietly. He was twenty-nine years old.

Coming up next: Siddhattha’s noble search, without Google.

Activities

Reference

[1] Jataka 75. Slightly different versions of this story abound. For example, one version said Siddhattha saw all four sights in one day, and another said he saw them over multiple days. Another version said that the king tried hard, but ultimately unsuccessfully, to prevent Siddhattha from witnessing suffering in the streets. In all versions of the story, though, the four sights exposed Siddhattha to fundamental suffering and caused him to decide to be an ascetic.

[2] Majjhima Nikāya 26.

[3] Ibid. The Buddha calls this the “ignoble search”.

Artwork by Colin Goh.

Sharing Joy and Wisdom with our Buddhist Art

Our team is honored to work with talented artists to create meaningful Buddhist art. To share these creations more widely, we are offering them on thoughtfully crafted merchandise. We hope these items can serve as gentle reminders and companions to inspire wisdom, compassion, and joy in daily life. [Learn More].

Explore our entire Buddhism.net collection here.

Explore the Four Sights that changed the Buddha’s Path design collection here.

Merchandise highlights from this design collection