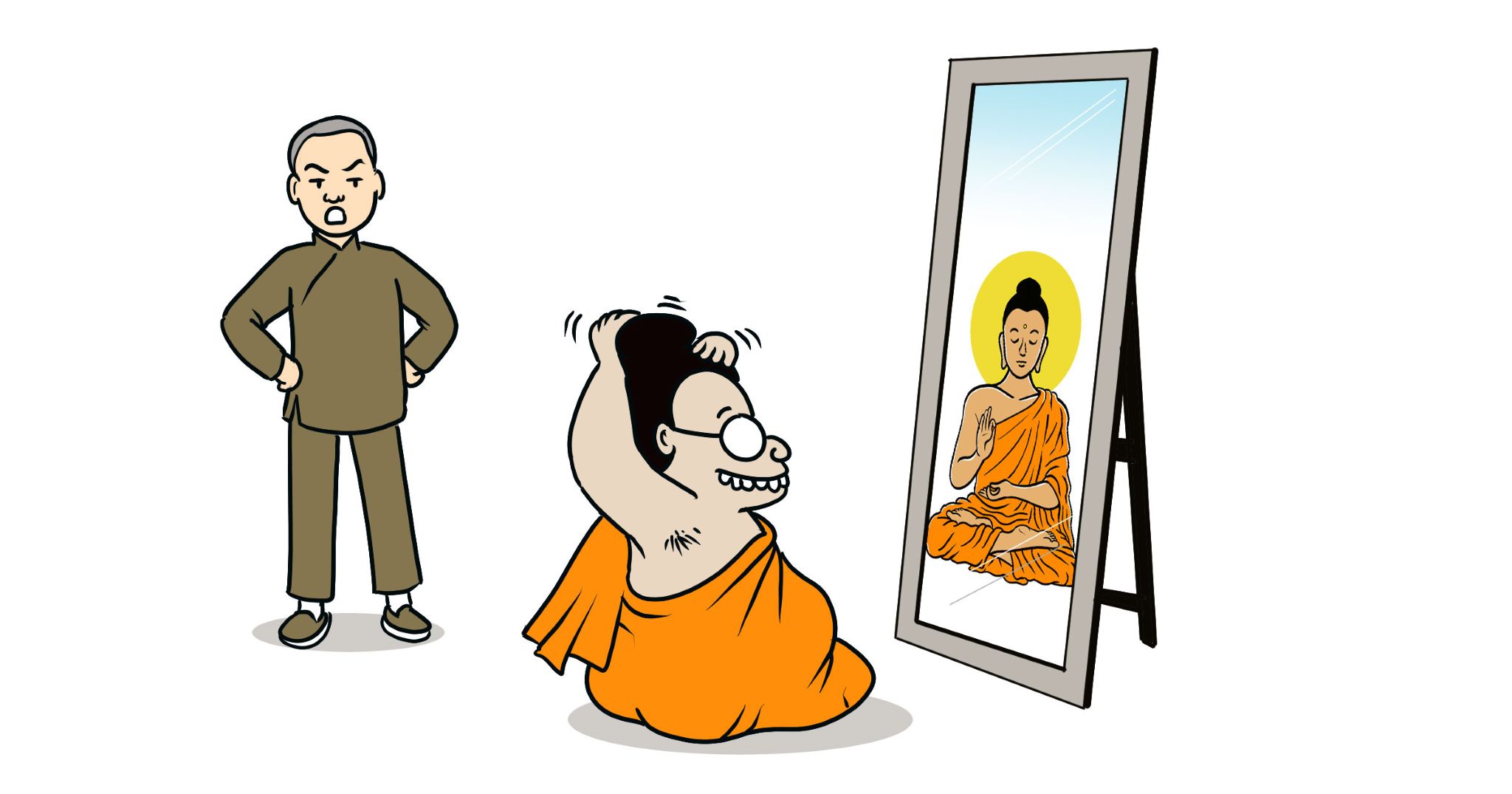

“I don’t think that is what the Master meant when he said, ‘Be like a buddha’.”

(Context: Come, See.)

This is a conversion story.

During the Buddha’s time, there was a famous lay follower of the Jain religion called Upāli. (This is not the same Upāli as the barber here. I know, right? People should really have unique names like Soryu Forall or Chade-Meng Tan.) Upāli engaged the Buddha in a debate, and at the end of it, he was so impressed with the Buddha that he asked to be the Buddha’s lay disciple, “From this day forth, may the Buddha remember me as a lay follower who has gone for refuge for life.”

What did the Buddha do? He gently declined. He said to Upāli, “A well-known person like you should act after careful consideration.” Now Upāli was really impressed, he said, “If any other master were to gain me as a disciple, they’d carry a banner all over Nāḷandā, saying: ‘The householder Upāli has become our disciple!’ But you tell me to consider carefully first. Now I’m even more delighted and satisfied with you.” And then he asked again to be his disciple.

This time, the Buddha laid down a condition, “For a long time, your family has been a supporter of the Jains. If you become my disciple, please continue to give to them.”

Now Upāli was even more impressed. He said, “If it were any other master, he would have told me to give only to his own people, and not to the others, but you tell me to continue giving to the Jains. Now I’m even more delighted and satisfied with you.” He accepted the condition and, for a third time, asked to be the Buddha’s disciple. This time, the Buddha accepted him.[1]

I am fascinated by the Upāli story. What it says is we do not care about adding more people who mark the box next to “Buddhism” on census forms, what we really want to do is help everybody in the best way for them, and if that best way is for them not to identify as “Buddhist”, we should encourage it. This coming from any religious leader would earn my approval, but coming from the founder of the religion itself, that inspires awe in me. This is also why many Buddhist teachers do not mind if somebody consider themselves Buddhists while they are simultaneously followers of another religion.

To be clear, it is not that we Buddhists do not care about sharing Buddhism widely, we do[2], but we do so with open arms, open hearts, and open minds.

Adding to that attitude is the definition of a “Buddhist”. A Buddhist is usually defined as a person who takes refuge in the Triple Gem (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha). Taking refuge simply means finding shelter, as in taking refuge at the closest hotel lobby when the storm gets really heavy. If you want, there is actually a ceremony you can partake in where you formally take refuge in the Triple Gem and declare yourself a Buddhist. Being raised in the tropics, I also joke that I take refuge in air-conditioning. Hence, I take four refuges. I brand myself as “taking 33% more refuges.”

One of the best things about this definition of a Buddhist is it does not exclude a Buddhist from simultaneously holding any other religion, as long as that other religion is okay with you taking refuge in the Triple Gem. If there appears to be any disagreement between Buddhist teachings and the doctrine of the other tradition, then we are invited to investigate to discover the truth, whether that turns out to be one, the other, or both, or neither. Buddhism is like a country that permits multiple citizenships.

Another definition of a Buddhist is one who understands the Four Noble Truths and actively practices the Noble Eightfold Path. I find this definition of Buddhist to be more useful and practical. Once again, this definition does not exclude a Buddhist from simultaneously practicing another religion.

I heard a modern-day story of an American who became a Buddhist, but since she came from a conservative Christian family, her family became upset with her, so every family gathering was filled with tension. After a while, she decided that when she was with her family, she would not try to be a Buddhist, she would instead try to be a buddha. And that worked. She realized that her family didn’t like her being a Buddhist, but liked her when she tried to be like a buddha.

So, the lesson, my friends, is don’t try to be a Buddhist, try to be a buddha. And if you do want to identify as Buddhist anyway, it is not a bad idea to continue to seek the truth in your original religious faith, if you have one. A number of my Christian friends have told me that learning and practicing Buddhism had helped them become better Christians. Theologian Paul Knitter even wrote an entire book expressing this sentiment, beautifully titled, Without Buddha I Could Not be a Christian.[3]

Soryu had an experience while living in Asia that surprised and deeply moved him. See, he grew up as a Christian boy in America where he learned that being Christian involves two things: 1. Identifying yourself as Christian and, 2. Holding on to a certain set of prescribed beliefs. When he encountered the Buddhist practitioners in Asia who he found most inspiring, he found that they did the exact opposite. First, they were too humble to identify themselves as “Buddhist” because, to them, being a “Buddhist” signifies embodying a deep practice and upholding high ethical standards, and even though they appeared like that to Soryu, they humbly did not claim anything. Second, to those people, what matters most is not what your beliefs are. Instead, what matters most is practice and virtuous behavior.

Soryu was very moved. He realized then that identity and beliefs are not the point. The real point is in the practice. Their example inspired him then, and continues to inspire him since. That is why as an abbot today, he frequently reminds his students that being a Buddhist is not about having an identity label, it is about practice.

The Dalai Lama himself frequently says he does not wish to encourage people to convert to Buddhism. When asked what his religion was, he said, “My true religion is kindness.”[4]

[1] Majjhima Nikāya 56.

[2] Soryu and I being among the worst offenders, I know.

[3] Paul F. Knitter, Without Buddha I Could Not be a Christian. Oneworld Academic (2013).

[4] Dalai Lama: Kindness, Clarity and Insight. Snow Lion Publications (1984).