In most religious traditions, miracles occupy a central place. In contrast, in early Buddhism, miracles are at best greeted with “meh”. In fact, Buddhist monks are even explicitly banned from performing miracles in public.

The monastic code the Buddha prescribed to the monastics is codified in a volume called the Vinaya (literally: “discipline” or “training”). It contains more than 200 rules for monks and nuns. The rules range from the essential to the seemingly trivial. The essential rules[1] forbid killing a human being, stealing, having sex, and lying about one’s own spiritual progress. And then there are the trivial rules, for example, a monk shall not keep a spare bowl for more than ten days, a monk shall not tickle another monk or play in water, a monk shall not lie down on a bed scattered with flowers, a monk shall not polish his nails, and so on. Out of these hundreds of rules, there is one buried in the middle of the “Minor Matters” (Khuddaka) chapter that almost literally flies off the page: a monk shall not perform miracles in public. Say what?

One really nice thing about the Vinaya is it tells the story behind every monastic rule, so we know the story behind this one,[2] and it’s quite fascinating. In the city of Rājagaha, a great merchant got his hands on a block of costly premium sandal wood. He had it carved into a bowl, tied a string around it, and suspended it high up at the end of a series of bamboo poles. And then he announced, “Whoever is perfectly enlightened and possess the psychic power to fetch this bowl down, the bowl will be given to him.” At that time, there were famous non-Buddhist teachers in India such as Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, and others. They each went to the great merchant and said, “I am perfectly enlightened and possessing of psychic powers, give the bowl to me.” And to each, the merchant gave the same reply, “If you can fetch down the bowl yourself, it is yours.” None of them did.

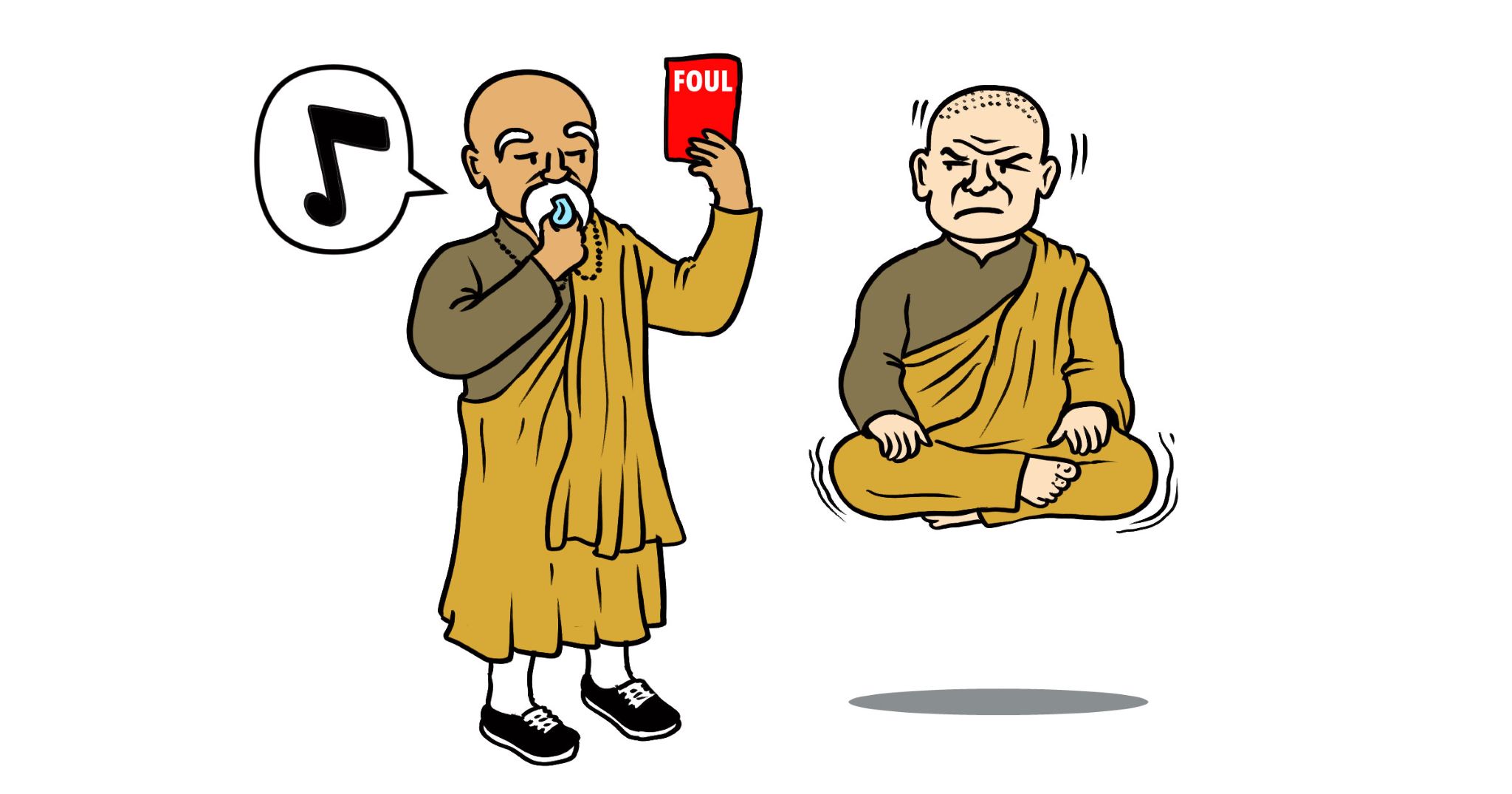

One fine day, two great enlightened Buddhist monks, Piṇḍola Bhāradvāja and Moggallāna entered the city for almsfood. As they walked near the bowl, Piṇḍola said to Moggallāna (presumably as a friendly tease), “Moggallāna, you are perfectly enlightened, you possess psychic powers, maybe you should get the bowl.” Moggallāna replied, “Piṇḍola, you too are perfectly enlightened and you too possess psychic powers, maybe you should get the bowl.” (It sounds like a joke, but that dialogue was actually documented in the Vinaya.) So Piṇḍola did. He levitated off the ground, flew all the way to the top of the cascade of bamboo poles, took the bowl, and for good measure, “circled three times round Rājagaha.” The people of Rājagaha witnessed it and made a huge commotion.

When the Buddha heard about it, he summoned Piṇḍola for what may be the most severe scolding ever given to an arahant by the Buddha. He compared Piṇḍola to a woman of negotiable modesty. He said to Piṇḍola, “Just like a woman exhibiting her privates for a miserable coin, you Piṇḍola exhibited your psychic powers for a miserable bowl.” From then on, the Buddha banned all displays of psychic powers to householders.

Yeah, holy wow. That was my reaction too.

You may wonder what happened to Piṇḍola after that. Well, nothing. For a start, Piṇḍola was already a fully enlightened arahant, he didn’t take the bowl because he was greedy, he almost certainly did it out of the purest of intentions: to inspire faith in the Dharma among the civilians, and surely the Buddha knew. In fact, despite the severe scolding, the Buddha didn’t lose confidence in Piṇḍola.[3]

So why did the Buddha ban the display of miracles to the civilians? Because it distracts them from the Dharma. Essentially, psychic powers and enlightenment are totally separate matters. It is possible for one who is fully enlightened to not have any psychic powers at all. The Buddha’s top disciple Sāriputta was the prime example, he was the wisest of all the Buddha’s disciples but had zero psychic powers. On the other hand, it is possible to develop psychic powers in your meditation and still be evil. The Buddha’s cousin Devadatta is the prime example. That story is coming up next.

Activities

- Reflect on this post with Angela:

- Reflect deeply on why you practice Buddhism. If the reason why you practice Buddhism is to boost your ego, manipulate or even harm others, then you’ve veered off the path and lost the essence of the Buddhist path and intention.

- What stood out to you from this article? Why?

References:

[1] Known as the pārājikas, which literally means “defeats”. If a monastic breaks any of these rules, he or she is considered “defeated” and is immediately expelled.

[2] Theravadin Vinaya Khandhaka 15.

[3] Fascinatingly, according to popular lore passed down in Chinese Buddhism, before the Buddha passed, he asked a small group of arahants to stay in samsara for the benefit of all sentient beings, and Piṇḍola was first on that list.

Featured image by Colin Goh.