The Noble Five-Factored Right Samadhi

Right samadhi refers to the four jhānas. The word jhāna literally means “meditation”, but when the Buddha uses that word, he is referring to a specific collection of four increasingly refined states of meditative absorption. That is why you often see jhāna translated as “absorption” and occasionally, as “meditation”. I decided to leave jhāna untranslated. The four jhānas are imaginatively named the first jhāna, the second jhāna, the third jhāna, and the fourth jhāna.

The four jhānas offer powerful stepping stones towards nirvana. The Buddha speaks very frequently of the jhānas, but I find his Discourse on the Five Factors[1] to be particularly helpful because he makes an explicit link between the jhānas and the “direct knowledge” that leads to nirvana, plus he gives colorful similes to illustrate his point.

First Jhāna

In the first jhāna, you are secluded from sensual pleasures and unwholesome states. That first jhāna gives you what the Buddha calls “rapture and happiness born of seclusion.” That is an extremely important stepping stone for you as a practitioner because it offers you the ability to reliably experience intense joy independent of sensual pleasures. Prior to this, you suffer from a reliance on sensual pleasure for joy, and in that sense, you are a slave to sensual pleasure. When you arrive at the first jhāna, however, you realize that you don’t need pleasant sensory experiences at all to be joyful, you can be ecstatically joyful just by sitting there with nothing happening.

To be fair, many seasoned meditators can already access a reliable stream of joy way before arriving at first jhāna, but in my experience, that pre-jhāna joy tends to be subtle and not strong enough to, say, displace my craving for chocolate, whereas the joy in the first jhāna is intense enough to significantly focus the mind and for the mind to tell itself, “This is all I need right now, I need nothing else.” Though highly focused, the mind is not totally unified at this point (that happens in the second jhāna), but it is sufficiently focused on the intense joy that, if you had never experienced jhāna before, may be the deepest meditative concentration you had ever experienced up till this point in your practice.

The pleasantness you experience starting from the first jhāna is why the Buddha calls the jhānas “pleasant abiding here and now”. Modern people may call it “blissing out”. But the first jhāna does something far more important than allowing you to bliss out: it gives you a vital insight that opens your door to nirvana. When you first learn Buddhism and read about the Buddha referring to sensual desire as a “fire” or “poison” that causes suffering, you may think it makes no sense at all. Satisfying sensual desire brings about so much pleasure, so how can sensual desire possibly be a cause for suffering? Surely it’s a cause for happiness. Once you experience the rapture and happiness in the first jhāna, however, the Buddha’s teachings on sensual desire suddenly make perfect sense.

First, you realize that this joy born of seclusion from sensual desire is more refined, sustainable, and satisfying than the joy that relies on fulfilling sensual desire. Second, and more importantly, you realize it does not have the same problematic side effects. Every shot of happiness that comes from fulfilling sensual desire necessarily plants a seed for future suffering in ways we talked about in an earlier post: no matter how many pleasant sensory objects we have, they eventually change for the worse (eg, they get old, or decay, etc), or we habituate to them (so even the very same objects become less pleasurable or even unpleasurable over time), or we will eventually lose them, or we lose the ability to enjoy them due to our own eventual sickness, frailty or death. Worse still, fulfilling sensual desire reinforces one’s reliance on and addiction to it. It is like scratching an itchy skin rash: you make it more likely that you’ll need to scratch it even more. Even worse still, scratching the rash does extra damage to it, and contributes nothing to its healing.

Hence, deriving happiness from sensual desire is like borrowing money from a loan shark who enjoys breaking knees: you get to enjoy the pleasure now, but you will surely pay much more than you get in the long term. Whereas experiencing happiness without sensual desire is like discovering that your rich grandparents left you a generous trust fund that gives you free money to spend every day. Once you realize you have that source of income, you would never want to borrow from a loan shark again, especially if the free money is more than what you can get from the loan shark. In the same way, once you have reliable access to rapture and happiness born of seclusion, you would understand why the Buddha calls sensual pleasure “low, vulgar, coarse, ignoble, and unbeneficial”.[2] The mind then naturally begins to let go of sensual desire. Or, as the Buddha says, “If you always have water, you don’t need a well.”[3]

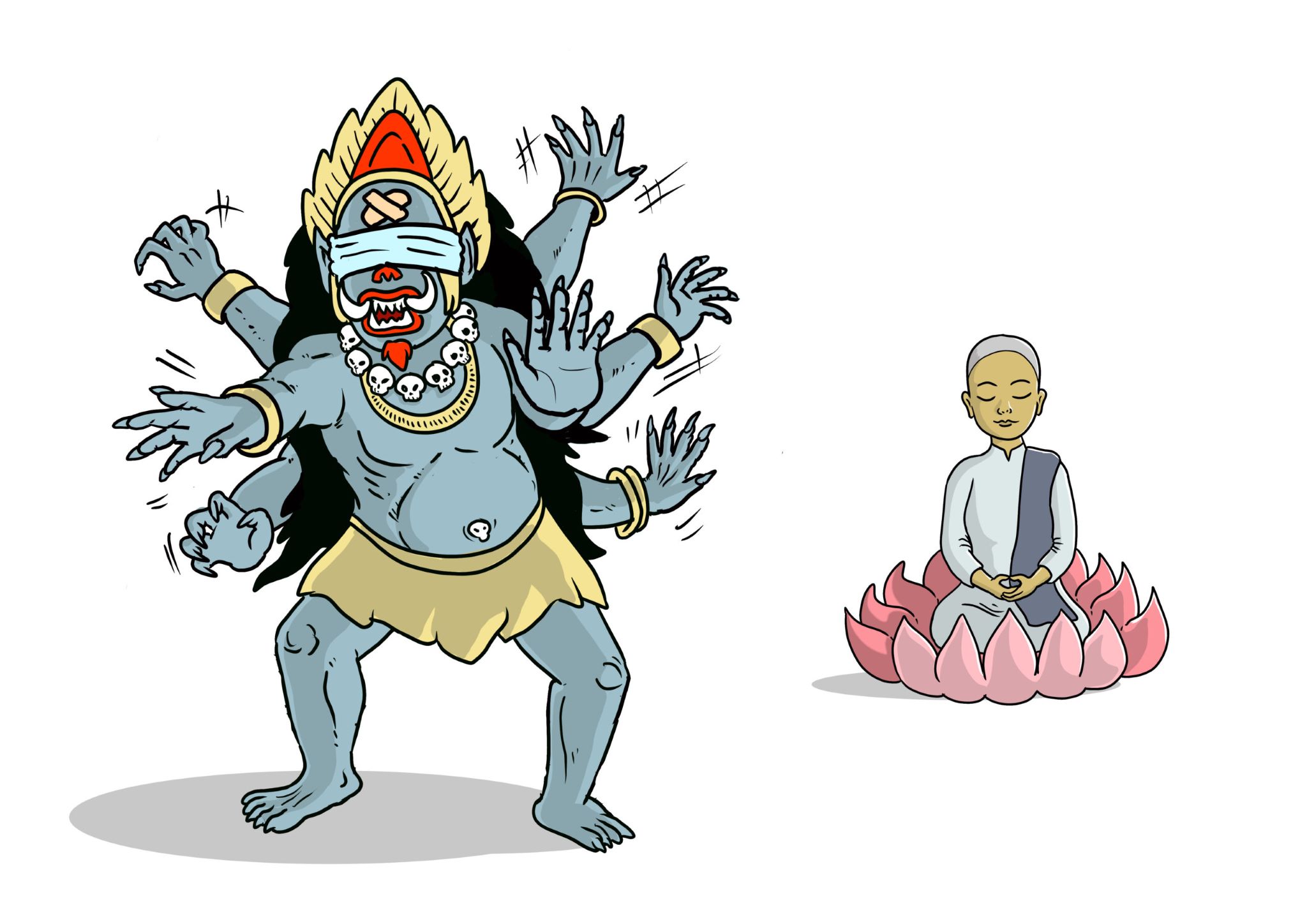

This is why the Buddha says the first jhāna is where sensual desire temporarily “ceases without remainder”, along with ill will and cruelty[4]. That is also why he calls the jhānas the place where “Mara and his following cannot go” and where the meditator has “blindfolded Mara”[5] (remember from an earlier post that Mara is the personification of all things bad). The implication of this statement is that the first jhāna serves you in two fantastic ways: it is not just a pleasant abiding for you, it is also a safe refuge where you gain total safety from Mara. In the first jhāna, a meditator knows, “I am secure from danger and Mara cannot do anything to me.”[6]

That is the reason the first jhāna is so important: it provides access to the inner joy that inclines the mind towards total freedom from lust and sensual desire, and thereby propels the mind towards wisdom and liberation from all suffering.

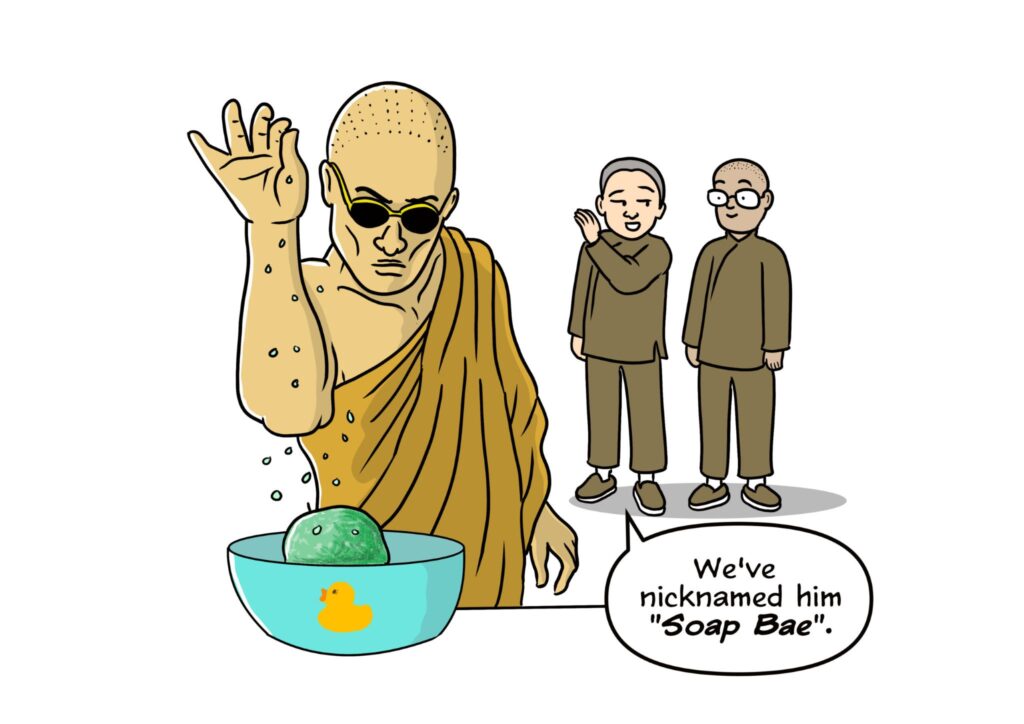

The Buddha’s simile of the first jhāna puts that inner joy on center stage. He says, “Just as a skillful bath man might heap bath powder in a metal basin and, sprinkling it gradually with water, would knead it until the moisture wets his ball of bath powder, soaks it, and pervades it inside and out, in the same way, the meditator makes the rapture and happiness born of seclusion drench, steep, fill, and pervade this body, so that there is no part of this whole body that is not pervaded by it.”

Second Jhāna

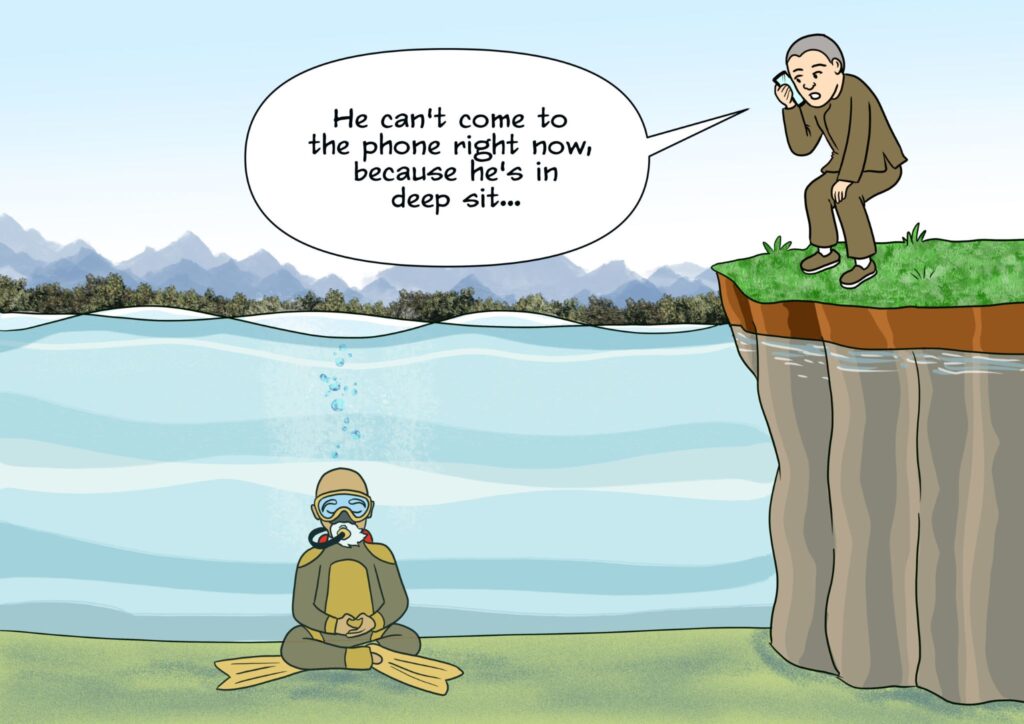

The second jhāna builds upon the first jhāna. In the second jhāna, all thinking subsides, the mind becomes placid and unified, and you experience what the Buddha calls “rapture and happiness born of samadhi.” This rapture and happiness is even more refined and sublime than in the first jhāna, but the most important contribution of the second jhāna is the strength of samadhi that allows for placidity and unification of mind.

It is this unification of mind that turns the mind into a powerful force for breaking ignorance and developing wisdom. It is like trying to start a fire with sunlight. If you merely put tinder out in the sun, it’s not likely to catch fire, but if you use a magnifying glass to collect sunlight into a tiny spot of tinder, then it may catch fire. It is also like uniting the mass of oppressed slaves against a tyrant’s rule. When the slaves are disunited, they have no chance against the tyrant’s oppressive regime, but once those slaves are united into a single force, then they can be free. In the same way, if you are dispersed internally, you are weak against Mara, but if your mind is internally unified, you become very powerful. The word samadhi literally means “to collect”, and the second jhāna is where this collectedness of mind begins to become a true force of wisdom to be reckoned with.

The Buddha’s simile of the second jhāna involves a lake, “Just as there might be a lake whose waters welled up from below with no inflow from any direction, and the lake would not be replenished by showers of rain, then the cool fount of water welling up in the lake would make the cool water drench, steep, fill, and pervade the lake, so that there would be no part of the whole lake that is not pervaded by cool water; so too, the meditator makes the rapture and happiness born of samadhi drench, steep, fill, and pervade this body, so that there is no part of his whole body that is not pervaded by the rapture and happiness born of samadhi.”

Once again, rapture and happiness takes center stage in this simile. The image of a lake which has no inflow from the outside, but wells up entirely from within, alludes to expanded breadth and depth of the inner joy, and to the experience of placidity and collectedness.

One key difference between the first two jhānas is illustrated in the similes. In the first jhāna, joy needs to be deliberately “sprinkled and kneaded in” until it saturates the body, while in the second jhāna, joy fills the body internally and spontaneously.

Third Jhāna

The third jhāna builds upon the second jhāna. In the third jhāna, rapture fades away and you are left with happiness. The Pali words that are translated into “rapture” and “happiness” are pīti and sukha, respectively. Pīti is also translated as “exhilaration”, “uplifting joy” or “energetic joy” and sukha is also translated as “bliss”, “pleasure” or “non-energetic joy”. Pīti and sukha are qualitatively different types of joy, with pīti marked by energy and excitement while sukha marked by a calm sense of pleasantness. In the third jhāna, the mind becomes much more tranquil than the second jhāna, and with that tranquility, pīti becomes uncomfortably exhausting and grating, so the mind gently abandons it and is left with sukha. With that, the Buddha says, “the meditator dwells equanimous, mindful and clearly comprehending.” It is not that those factors were not present before, but that with increasing tranquility and unification of mind, those factors strengthen massively and become prominent enough to start taking the foreground.

Hence, the most visible contribution of the third jhāna is the tranquilization of mind that leads to the abandoning of pīti, but more importantly, with a mind well pacified and unified, the factors of mind that lead directly to wisdom strengthen and come prominently into the foreground: equanimity, mindfulness and clear comprehension, supported solidly by sukha. For that reason, the Buddha says one who dwells in the third jhāna is declared by the noble ones as: “equanimous, mindful, dwelling happily.”

The Buddha’s simile of the third jhāna is, “Just as in a pond of blue or red or white lotuses, some lotuses that are born and grow in the water might thrive immersed in the water without rising out of it, and cool water would drench, steep, fill, and pervade them to their tips and their roots, so that there would be no part of those lotuses that would not be pervaded by cool water; so too, the meditator makes the happiness divested of rapture drench, steep, fill, and pervade this body, so that there is no part of his whole body that is not pervaded by the happiness divested of rapture.”

This simile is similar to the second jhāna, but with one visible addition: the lotuses. Is there a significance to the lotus imagery? Very likely so, since the Buddha uses the lotus as the symbol for buddhahood itself. In a conversation with brahmin Doṇa, the Buddha famously said in verse:

“As a lovely white lotus

is not soiled by the water,

I am not soiled by the world:

therefore, O brahmin, I am a buddha.”[7]

My own understanding, based on the description of the third jhāna, is that the lotuses in the simile alludes to the wisdom factors coming to the fore. That is the most important contribution of the third jhāna.

As usual, Soryu offers a complementary but deeper and more nuanced understanding of the analogy. He thinks the key point about the analogy is aliveness (of the lotuses), and it is exactly this aliveness that is the wisdom. He points out in his usual, poetic Zen style, “It’s no longer that we are just doing what we learned we should. The path knows how to walk itself. It shifts from dead knowledge to living wisdom.” In addition, because of that aliveness and wisdom, the joy also appears to expand: it is now experienced as if it is everywhere, both within and without, like the cool water that is both within the lotuses and also outside in every direction.

Fourth Jhāna

The fourth jhāna builds upon the third jhāna. In the fourth jhāna, the mind abandons even the sukha (happiness) and rises above and beyond pleasure and pain, joy and dejection. Equanimity is perfected. In that state, something extremely important happens: the mind now possesses mindfulness purified by equanimity. The meditator “sits pervading this body with a pure bright mind, so that there is no part of his whole body that is not pervaded by the pure bright mind.” It is this mindfulness purified by equanimity that directly enables the penetration into the “direct knowledge” that leads to nirvana.

The Buddha’s simile of the fourth jhāna alludes directly to this purity of mindfulness. The simile is one where a man, after having taken a bath, “sits covered from the head down with a white cloth, so that there would be no part of his whole body that is not pervaded by the white cloth; so too, the meditator sits pervading this body with a pure bright mind, so that there is no part of his whole body that is not pervaded by the pure bright mind.” [8]

Jhāna teacher Leigh Brasington suspects this simile is more literal than most people think. He said when one enters the fourth jhāna upon establishing very strong concentration, one’s visual perception is very bright, even with eyes closed. He said imagine on a very bright and sunny afternoon, pitching a small white tent in the middle of an open field, and sitting inside that tent: your visual sense will be dominated by white brightness in all directions, and that is the visual experience. Soryu agrees that the visual perception is very bright, yet somehow not blinding, but more importantly, the mind itself is bright. Every aspect of consciousness is bright, not just the visual field. The practice is to be sure that this bright mind pervades somatic experience.

Direct Knowledge

The final step is to make use of this pure bright mind to acquire “direct knowledge”. The way to do it is to attend to the object of interest with this turbocharged mind. This is a mind that is unified with perfect attentional mastery, sharpened with perfect mindfulness, pacified with perfect tranquility, and unencumbered by hindrances, pleasure or pain, like or dislike. This is the mind most perfectly conducive to wisdom.

With that power of mind, the Buddha says, “a meditator grasps well the object to be reviewed, attends to it well, sustains it well, penetrates it well with wisdom.” He gives a simile of a person looking at another from a higher point of view, and because his point of view is elevated, he can see better. “Just as one standing might look upon one sitting down, or one sitting down might look upon one lying down—so too, a monk has grasped well the object of reviewing, attended to it well, sustained it well, and penetrated it well with wisdom.”

Yes, it’s true that the jhānas are a great place to be just to bliss out and enjoy a “pleasant abiding here and now”. Indeed, when the Buddha was asked whether “an exclusively pleasant world” can be realized, he answered, yes, and that exclusively pleasant world is the fourth jhāna.[9] In fact, the Buddha even encouraged it. He said, “The four jhānas are called the bliss of renunciation, the bliss of seclusion, the bliss of peace, the bliss of enlightenment. This kind of pleasure should be pursued, developed, cultivated, should not be feared.”[10] But far more important than that is using the jhānas to take the mind to a place where is it perfectly conducive to wisdom, and then using it to gain direct knowledge into nirvana. The Buddha calls it the noble five-factored right samadhi: the four jhānas, and the gaining of direct knowledge using the fourth jhāna as the base of operations.

In summary, these are the five parts of the five-factored right samadhi, and the essential stepping stones each offers you, on your path to nirvana:

- In the first jhāna, you gain the life-changing ability to abide in rapture and happiness independent of sensual pleasures.

- In the second jhāna, thinking subsides completely and mind becomes placid and unified.

- In the third jhāna, mind becomes tranquil, rapture fades away, and wisdom factors (mindfulness, clear comprehension, and equanimity) come to the fore.

- In the fourth jhāna, mind rises above and beyond all pleasure and pain, equanimity is perfected, and most important of all, mindfulness is purified by equanimity. The Buddha calls it “pure bright mind”.

- Using this pure bright mind, gain wisdom and direct knowledge leading to nirvana.

The Buddha offered three similes relating to the end result of this process. The first is a water jug full of water has been set out on a stand, a strong man can easily tip it in any direction and spill the water. In the same way, a meditator equipped with the jhānas has a strong mind that can realize any insight as easily as the strong man can tip the jar. The second simile is similar: a square pond on level ground filled to the brim, a strong man can open any of the four walls and the water will rush out. The third simile involves a masterful charioteer riding a chariot harnessed to thoroughbreds, driving on flat ground, he can easily drive in whichever direction whenever he wants. A meditator equipped with the jhānas is like that masterful charioteer.

In the same discourse, the Buddha states by applying your super-duper jhāna mind appropriately, you can “with the destruction of the taints, realize in this very life with direct knowledge the taintless liberation of mind and liberation by wisdom, and having entered upon it, dwell in it.”

In other words, my friends, nirvana.

Activities

- Reflect on this post with Angela: Happiness from external sources is coarse when compared to joy experienced when the mind is free from the five hindrances, as described in the four Jhānas. Yet, most of us do not experience these sublime states in our daily lives. Instead, we experience an overactive mind. The bad news is we are in no way touching the depths of our mind’s potential. The good news is our mind’s potential is unlimited. Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh says, “the way out, is in”. Into what? Into the depths of our mind and away from external sensual pleasures. What insights, learning, or reflection came up for you from this article?

References

[1] Pañcaṅgika Sutta (Aṅguttara Nikāya 5.28).

[2] Majjhima Nikāya 139.

[3] Udāna 7.9.

[4] Majjhima Nikāya 78.

[5] Majjhima Nikāya 25.

[6] Saṃyutta Nikāya 9.39.

[7] Aṅguttara Nikāya 4.36.

[8] The version of this simile in the Pali Nikāyas does not mention the bath, but one in the Chinese Āgamas does.

[9] Majjhima Nikāya 79.

[10] Majjhima Nikāya 139.

Featured image by Colin Goh.