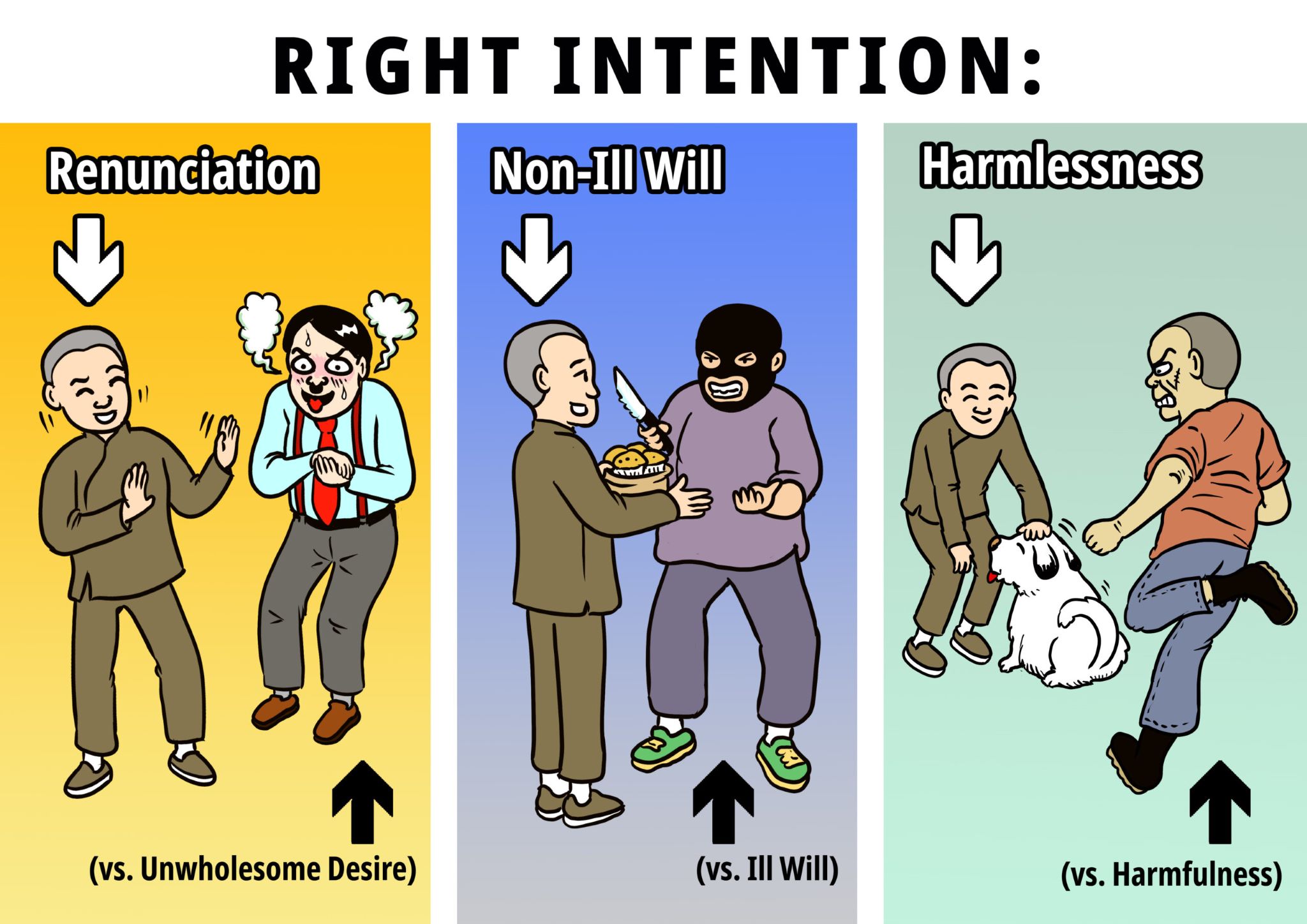

Right intention means these three intentions: renunciation, non-ill will, and harmlessnesss.[1] They are the direct opposite of three intentions that result in suffering: unwholesome desire, ill will and harmfulness. Renunciation does not just mean giving everything up and checking yourself into a monastery. It more generally refers to letting go, and it covers an entire spectrum, ranging from letting go of addiction, to letting go of unwholesome habits, to yes, checking yourself into a monastery, all the way up to the letting go of samsara.

A beginner may think that renunciation hampers joy. Counter-intuitively, all three parts of right intention, including renunciation, are designed to increase joy. They do so by trading in a less refined joy for a more refined one. A childish example is when I was a child, I found a lot of pleasure in eating cheap sweets, but as an adult, I find them unsatisfying, so I give them up for high quality chocolate. In a similar way, you will find in this book that the practice of Buddhism involves the discovery of deep sources of immense inner joy, and all three parts of right intention facilitate access to that inner joy. The greater the renunciation, good will and harmlessness, the greater the access.

As compelling as that is, something else makes right intention even more important: intentions beget thoughts, and thoughts change the inclination of the mind, either towards or away from nirvana. In one discourse,[2] the Buddha talked about having two kinds of thoughts before his enlightenment: one arising from wrong intention, and the other arising from right intention. He realized that thoughts arising from wrong intention “lead to affliction for myself and others; obstruct wisdom; cause difficulties; lead away from nirvana”, while the other kind leads to the reverse. He further realized that “whatever one frequently thinks and ponders upon, that will become the inclination of his mind.” Hence, he decided to abandon thoughts arising from wrong intention.

As usual, the Buddha has a delightful simile: “In the autumn, when the crops thicken, a cowherd would guard his cows by constantly tapping and poking them on this side and that with a stick to prevent them from straying into the crops. Why? Because he sees that he could be punished if that happens. In the same way, I saw danger, degradation and defilement in the unwholesome thoughts.” In addition to abandoning unwholesome thoughts, Siddhattha also cultivated the wholesome ones, the ones arising from renunciation, good will and harmlessness. With that, the mental pre-conditions for arriving at nirvana were eventually established, “Tireless energy was aroused in me and unremitting mindfulness was established, my body was tranquil and untroubled, my mind concentrated and unified.” That, my friends, is why right intention is important.

Soryu has a unique take on right intention. He thinks of right intention as the Buddhist edition of the “American Dream”, as in, the ideal lives we want to aspire for. In the case of this “Buddhist Dream”, it means three things: 1. to be delightfully happy whatever our physical and material circumstances, because our dream is to let go of everything, 2. to always have a joyful loving heart for all, because our dream is to never engage in hatred, and 3. to always be joyfully benefiting all, because our dream is to never harm anyone. In other words, a lifestyle of joy, meaning and fulfillment is promised by the three ways of right intention.[3]

I’ll say it again in case you missed the significance of it: one who lives a life of right intention lives a life of joy.

Soryu frames right view as a statement of facts – the way things are – and right intention as the dream of the good life – how we should behave in response to those facts (“right is” and “right ought”, he half-jokingly calls them, or at least I think he is half-joking), and the other six parts of the Noble Eightfold Path as the way to fulfil this “Buddhist Dream”.

Activities

References

[1] Saṃyutta Nikāya 45.8.

[2] Dvedhāvitakka Sutta (Majjhima Nikāya 19).

[3] Soryu’s framing of “Buddhist Dream” is grounded in the etymology of the word saṅkappa, since saṅkappa closely relates to the word kappeti, which means “to create, to build”.

Artwork by Colin Goh.